In the early 1970s, those in the know of the mail-art network might have found their lucky boxes stuffed with an image of a handsome young man. He had a throbbing dick and his neck in a noose. The man went by Jimmy, or Jim, DeSana, or de Sana, or De Sana—what’s in a name? The photograph was by him too. DeSana got around; he seemed to know everybody who was or would be anybody in American downtown culture, and so if you were one of them you might have gotten it from him directly. Mail art was amazing that way: if you were connected, your postal carrier might deliver a minor masterpiece or intriguing experiment, sent by an artist on the other side of the world or a few blocks away, as frequently as you might stumble upon one in a gallery.

If not, you might have seen the photograph in the February 1974 issue of File, the Torontonian queer collective General Idea’s ground- and boundary-breaking magazine. Or, on the cover of Vile, Anna Banana’s baiting File lampoon. If you didn’t know the face, you could grok the aesthetic: The noir rubbernecking of Weegee, in content. Its tone was Arbus. Its form, the way his arms pulled back like Hermes and chest stretched like Christ, evoked the life-and-death magic of Kenneth Anger. Its refusal to remain as a single ownable object, with a singular meaning, pulled in strategies of Surrealism, Fluxus, and punk, while its instant appeal was pure Pop. It was abject, funny, and oddly abstract. It should be unforgettable.

Submission, the Brooklyn Museum’s welcome retrospective of DeSana’s photography and video, is overdue in the sense that the COVID-19 pandemic delayed it by almost two years and also because it should have happened decades ago. The artist Laurie Simmons, DeSana’s friend and collaborator, has been working for years to archive and protect his work—and champion his legacy. At the show’s long-awaited opening in November 2022, she gave a toast to its curator Drew Sawyer, noting that the work was waiting for him. We should be glad they found each other.

DeSana’s vision feels as much of its own moment as it does ours; a photo like Sink (1979), in which a corseted figure bobs for something in a sink full of bubbles is so smart, and stupid, that it achieves timelessness. At a moment in which queer visibility is once again increasingly life-threatening, it’s admirable that the museum mounted this show on the ground floor—in a space near the entrance that was formerly the gift shop—for all the world to see. Sawyer’s nimble installation sidesteps prurience and preciousness, moving viewers through rooms of insouciant early 1970s photos to the hallucinatory, dignified work DeSana made before dying of AIDS-related complications in 1990. Without succumbing to the self-congratulatory drama of a rescue mission, Submission recoups what may have otherwise been lost.

DeSana was born in Detroit in 1949 to middle-class suburbanites, who raised him and his brother in Atlanta. His mother was a strict Methodist; his father abandoned the family as DeSana entered adulthood. While studying art at Georgia State University, DeSana began making precocious, conceptual photography of suburban houses, generally banal, and of his friends, often naked. But his final thesis, 101 Nudes (1972), is a landmark. Likely taken with a Leica IIIf and lit by a flash, as Sawyer notes in his catalog essay, the portraits form a kind of fanzine of queer friends. DeSana shows off their muscles like he’s making Physique Pictorial, or crouches and crops their bodies like a funnier Man Ray. A drag queen looks right into the camera, bold; a man shoves his face into a pillow, ass beckoning. Bodies are unstable, and DeSana captures how funny, and how frightening, that can be, and how those two emotions comprise desire. Sawyer hangs these prints on the wall like Teen Beat posters in a teenage bedroom. It’s hard not to be a fan.

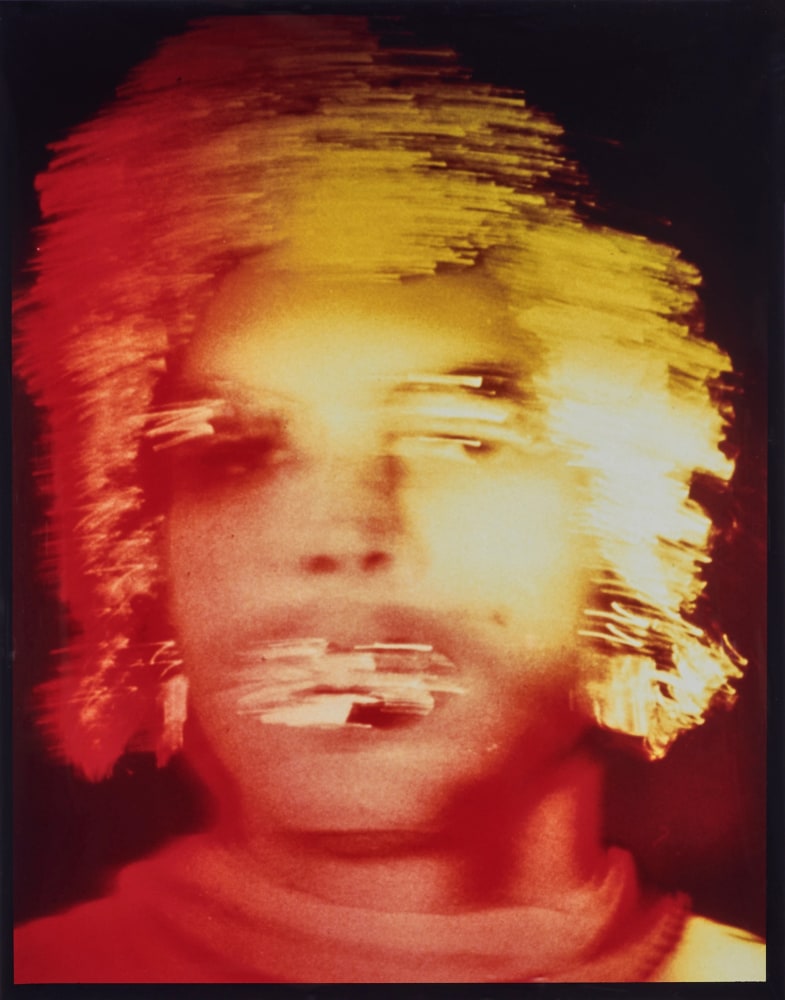

Evidence and expression in hand, DeSana moved to New York in 1973 and spent the 1970s hanging out at the nightclubs downtown, enjoying the spectacular squalor of Times Square, and working rooms further uptown, like Robert Stefanotti’s gallery on 59th Street. He took early portraits of the Talking Heads and Laurie Anderson and Debbie Harry that quickly established their personae. His non-star subjects also seem like them. Submission positions these images like family portraits. Often, they are black and white, stark as his earlier autoerotic provocation, sometimes lit by a single bulb on the sideline. The lighting doubles their bodies into an architecture for their charisma, or a shadow they couldn’t shake off. When he worked in color, it was those of candy wrappers, neon, the camp saturation of advertising. Recognizable but not realism.

With a wink to the commonalities of darkrooms and backrooms, Sawyer built a red-light district for DeSana’s extensive investigations of BDSM, in which piss is expelled and enjoyed, and gimp-masked figures kneel in toilets or near dog bowls. In Party Picks (1981), toothpicks stuck into gums between teeth make a crown of thorns around a gasping mouth, or maybe make that mouth St. Sebastian’s wound. Cardboard (1985) offers a room with a single, lurid red band of light and corrugated carboard that slices a bending body. In such a place, you might think of Samuel Steward’s card catalog of his conquests, or if Flavin’s work is really about its shadows, or what to do with that butt. DeSana’s frisky, familiar portraits reject the po-faced posing of Mapplethorpe and the social-climbing sadism of Helmut Newton. He gets that such proclivities are mind games played with bodies and bets you might want to play them too.

Toward the end of his life, DeSana went monumental. Soft Ball (1985) puts a toy on a plinth and conjures an awe somewhere between Ansel Adams and Kubrick. Grill (1985), captures its titular forger of suburban masculinity bent over in blue. It looks like a mammoth cage. It might be about his childhood. Sawyer provocatively asks viewers to return to the beginning when exiting the show, refusing to let death have the last word. Now, it’s almost impossible to resist the sense that DeSana was just getting started. But we must. He did so much, and it was enough.

A decade after DeSana photographed himself hung in a noose, he made Stitches (1984). The self-portrait shows off his sexy Calvin Klein briefs, and also the thick, roping scar he earned when HIV infection (and celiac disease) ruptured his spleen. The sutures are both evidence and prophesy, but really, they’re just a part of him and his art—what he made from mortality. I’m thinking as I write this of the selfie Daniel Davis Aston posted just before he was shot dead at Club Q in Colorado, in which he caresses the stitches of his top surgery. DeSana claimed the right to make bodies as he saw fit. Submission demands we now also have that right. His work is immortal in its unabashed mortality. We might live that way too.